Opinions of the US Supreme Court – Does Word Count Correlate to Citations?

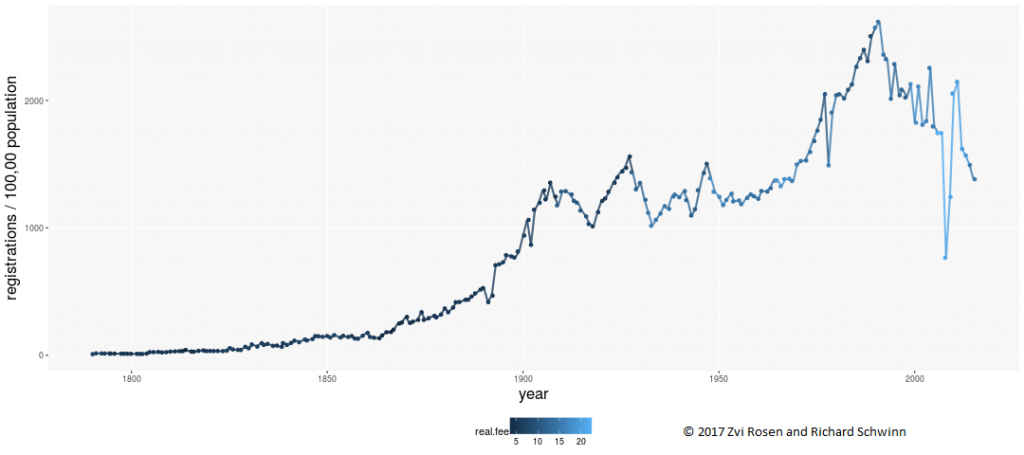

As part of a symposium on forgotten cases in intellectual property with the Syracuse Law Review, I recently wrote a short history of the US Supreme Court’s 1879 decision in Perris v. Hexamer, entitled How Perris V. Hexamer Was Lost in the Shadow of Baker V. Selden. Perris is essentially forgotten today, but it has somewhat similar facts and holding to Baker v. Selden, decided the following year. The decision is less than 1,000 words, so it’s pretty easy to give it a read, but essentially the Court held that the legend/key to a fire map showing what different symbols meant was not protected by copyright, and that using the same colors and symbols as a competitor’s map did not constitute infringement either. In some ways this decision is even more relevant than Baker (concerning the copyrightability of accounting ledgers) to the copyright questions raised in cases like Google v. Oracle, among others. However, Baker keeps being cited (hundreds of times in the past few decades alone), while a citation in 2016 by the 9th Circuit was the first citation to Perris in 3+ decades. I wanted to figure out why. Given that Perris is a fairly short opinion and Baker is an average-length opinion, I figured perhaps just the length of the opinion led Perris to be ignored, as presumably other short opinions would be ignored.

This question naturally led me to try to answer a broader question than I actually needed to. I assumed that there must be public databases out there of the number of words in an opinion, along with the number of citations to that opinion. However, while there has been some scholarship on the question, no public database of this sort exists.1 Accordingly, with help from my law school classmate Corey Mathers, I decided to try to assemble it. Paid databases like Westlaw and Lexis were not options, but the website Courtlistener.com (a project of the Free Law Project) does have the entire US Reports, along with citation tracking. Accordingly, we decided to build our database from that site.

Accordingly, our data is here (zipped CSV), with data on every Supreme Court decision, including word count, number of citations to authority in the opinion, and number of citations to the opinion (as well as caption and year). We removed cases that have less than 200 words, which are typically not real decisions but are rather summary orders like grants of certiorari.

However, the data has some weaknesses, and should really be considered more of a first step than a definitive resource. By far the most significant weakness stems from the holdings of Courtlistener – while it has many recent decisions and all Supreme Court decisions, it is missing most caselaw from before 1950 or so. Accordingly this creates a bias in favor of more recent cases, but at least the bias is uniform across all cases. Ideally the data could be recreated from a database with more decisions. Also, the word count for pre-1880 decisions frequently includes lengthy arguments of counsel as well as the actual decisions. There are several other smaller issues as well, all of which could be resolved by re-running the query we ran on a database with full coverage of federal and state decisions.

Usually these posts have been a chunk of information, but this one is really more open-ended, since I know the data we created is deeply incomplete – it was acceptable for purposes of my paper but could be improved. What would be good next steps for developing the data? What other data should we be trying to generate (only data that can be done automatically, nothing that would require manual review beyond error-checking)?

- There is the Supreme Court Database, which has extensive information on cases, and is of special interest to political scientists and legal historians. However, it does not contain this information. ↩