25

Nov

2016

The Firing of Rufus L.B. Clarke from the Patent Office in 1895

Both IP historians and con law fans will find interest in this post, about an event that seems to have been poorly reported in the histories up to this point, about the President’s power to remove a senior IP official in the government.

Rufus L.B. Clarke is best remembered, if he is remembered at all, as one of the framers of the Iowa Constitution of 1857, and for arguing for racial equality at that Constitutional Convention.1 Following this Clarke went to Washington, D.C., where he became one of the three Chief Examiners in the Patent Office in 1869, by appointment of the President and consent of the Senate.2 The Board of Examiners-in-Chief were not in charge of examination, but instead constituted a board of appeal of examiner decisions on patents, who formed an intermediate step before a decision would be appealed to the Commissioner.3

Clarke’s career was somewhat bumpy at the Patent Office, and in 1875 the Commissioner of Patents attempted to remove him, as Clarke explained in a letter to President Grant.4 This effort at his removal apparently was unsuccessful, and Clarke remained at the Patent Office as one of their Chief Examiners until 1895, when the President informed Clarke that his employment as Examiner-in-Chief was terminated, effective upon the confirmation of his successor. He was replaced by one J.H. Brickenstein.

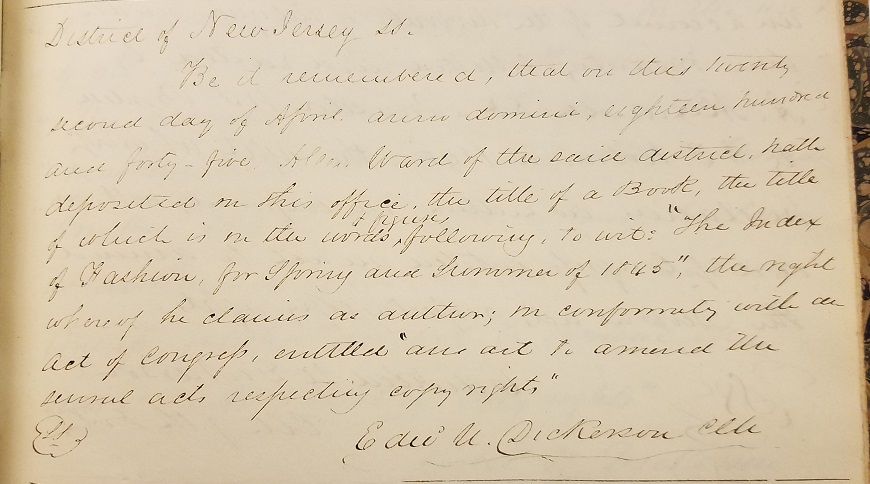

Clarke was born in 1817, and thus at this point was nearly eighty years old. Nonetheless, he elected to tenaciously fight his removal. Clarke submitted to the Senate a a brief and other supporting documents (PDF, 12 MB) laying out the background of his case, and arguing that the President had no Constitutional power to remove him.5 Clarke made a general argument that the President lacked the authority to remove executive appointees, but also a more specific argument that as a judicial officer, the President lacked the authority as a remove him. Brickenstein submitted his own memorandum to the Senate in this matter (included in the same PDF file above), arguing that while the Board of Examiners-in-Chief may have been a judicial tribunal, this did not make it an Article III Court with all the protections from removal that the Constitution provides.

There is no documentation of the Senate taking a particular action in regards of Clarke’s petition, and the Official Register of the US Government for subsequent years shows that Brickenstein remained as an Examiner-in-Chief while Clarke did not regain this position. Clarke lived another fifteen years after his removal, passing in 1910. The controversy has not generated extensive attention, but it is an interesting one, both in terms of the structure of the Patent Office and in terms of the Presidents authority over quasi-judicial officers.

- Robert R. Dykstra, Bright Radical Star: Black Freedom and White Supremacy on the Hawkeye Frontier 161 (1993). He was also a delegate to the 1860 Republican Convention that nominated Abraham Lincoln. ↩

- Dykstra refers to his subsequent career as a series of “anonymous patronage jobs” in Washington. Id. at 239. ↩

- This was a creation of the Patent Act of 1861, 12 Stat. 246 ↩

- John Y. Simon, et al, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant: 1875 at 220. ↩

- Parts of this file were reproduced in a print by the Senate Committee on Patents for the 54th Congress, and were subsequently reproduced as part of a CIS Microfilm, now on Proquest Congressional (for subscribers). It is at CIS Number S3629, SuDoc Number Y4.P27/2:C55. ↩