The Copyright in “Little Women”

“An honest publisher and a lucky author, for the copyright made her fortune, and the ‘dull book’ was the first golden egg of the ugly duckling.” – Louisa May Alcott, 1885

With a new movie version coming out, Louisa May Alcott’s novel Little Women is once again in the news, often with some conversation of how Alcott’s publisher urged her to keep the copyright in her work, earning her a fortune. But the story of her copyright is rarely explored beyond that, and I think it’s an interesting one, in that it spans multiple eras of copyright history in a way only a few other works did. It’s also a useful research case study for those interested in using copyright records for historical and literary research. I’ll admit I haven’t seen the film yet, but I’m told that it has a great scene about copyright – I’ll have to check it out.

I’m also informed that the Library of Congress has an exhibition of some of the copyright deposits made by Louisa May Alcott, catch it while it’s still up. The discussion continues below…

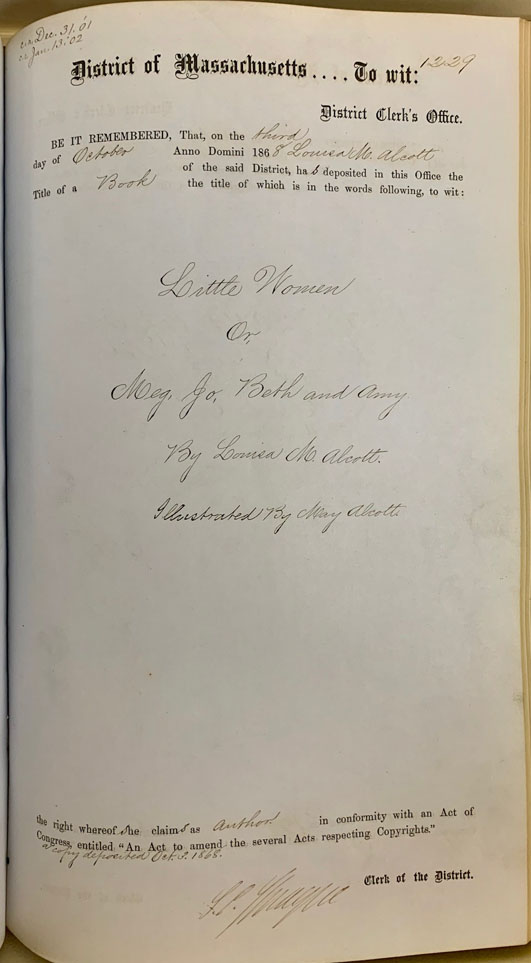

Prior to 1870, copyright registration would have been with the local federal District Court. And in 1868 that’s just what Louisa May Alcott did, filing the below copyright registration with the clerk of the U.S. District Court for Massachusetts and paying the fee.

As the ledger notes, she was filing the claim on her own behalf as author (the forms back then were “he” by default, with extra room for the “s”), and filed a copy with the clerk simultaneously. This itself was somewhat unusual – copyright registration was usually done prior to publication, and usually the title page was a rough mock-up, not the finished work. The Library of Congress searched and didn’t find a title page, which could mean that it hasn’t been found yet, but I kind of suspect that because she deposited the whole book at the time, the Clerk decided a printed title page was unnecessary. Under the 1831 Copyright Act the registrant deposited a copy with the clerk, who would then forward deposits in bulk to Washington, DC. 1 Pursuant to the amendments to the U.S. copyright law in 1859, 1865, and 1867, Alcott would have also needed to deposit copies with the Patent Office and Library of Congress; ledgers of deposits for those institutions are both now held by the Library of Congress Rare Book Room. Note that I’m not positive about the notations on the upper left corner – they could indicate the renewal dates, but those don’t match with the actual renewals, discussed below. It could also refer to additional copies being requested.

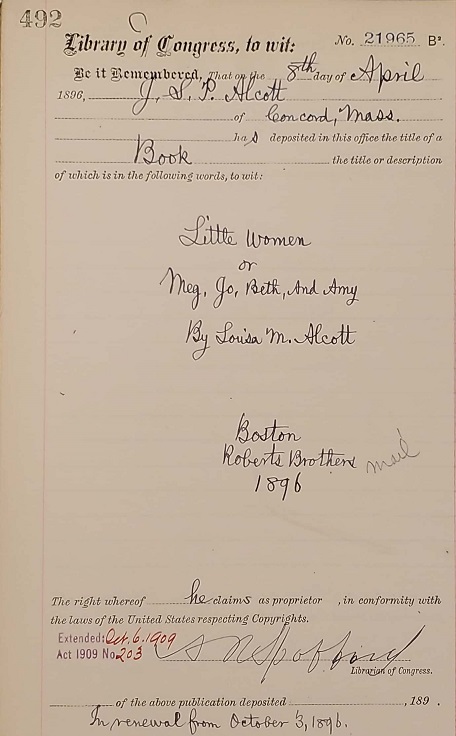

The book was a terrific success. She subsequently published a second volume of Little Women, and registered it separately for copyright the following year (all documents reproduced here have an analog for Volume 2, even though they’re been published together ever since). The copyright term at the time was 28 years plus a 14 year renewal for the author or her heirs. Louisa May Alcott never married, but late in her life she adopted her nephew John S. Pratt, likely in part so her family could continue to enjoy the benefits of her copyrights. 2 She died in 1888, and on April 8, 1895 John S.P. Alcott filed a renewal of the copyright in Little Women, for a 14 year renewal term. In 1870 copyright had been moved entirely to the Library of Congress, but records of renewals before 1898 were not included in either the Catalog of Copyright Entries or the Copyright Card Catalog. However, I was able to find the record of this renewal based on the information in the Catalog of Copyright Entries from 1909 due to a subsequent extension, discussed below.

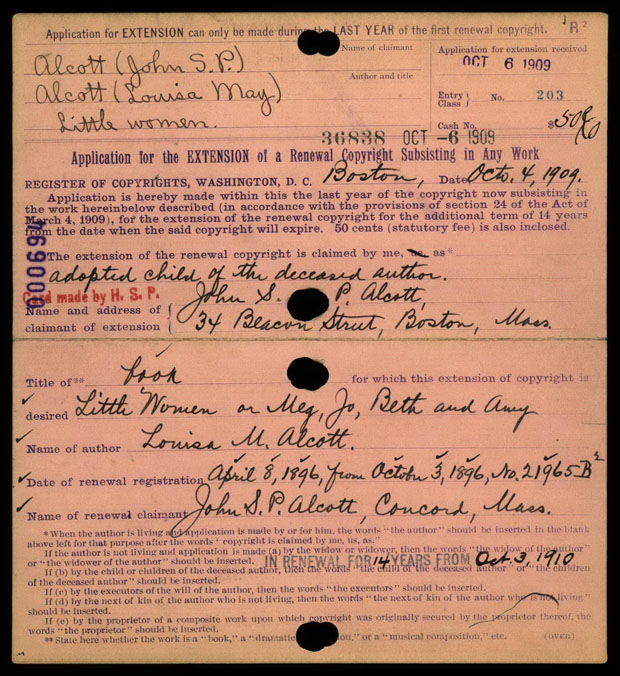

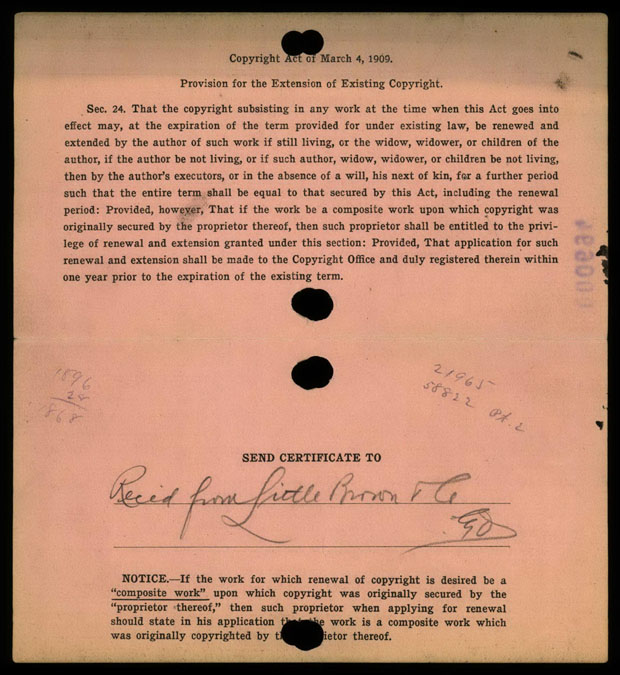

In 1909 the expiration of the copyright renewal was looming, but in that year the renewal term was extended from 14 to 28 years. Section 24 of the 1909 Act required that works within a year of expiration under the previous term have an extension filed, and John S.P. Alcott filed the requisite extension a few months after that law passed, on October 4, 1909, which was included in the Catalog of Copyright Entries as well. A sharp-eyed reader will note that this was the very first day of the possible renewal period – the original registration had been filed 41 years and a day earlier. The extension became effective October 3, 1910.

Interestingly, the rear of the 1909 Extension shows that the extension was actually being done by Little, Brown & Co., which had taken over Alcott’s publisher Roberts Bros. in 1898.

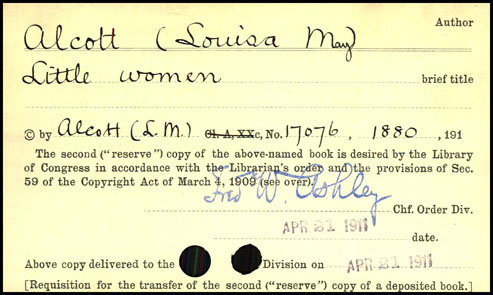

Afterwards, the Library of Congress began requesting additional copies of her books, through the provisions of the 1909 Act that allowed for the request of additional “reserve” copies of copyrighted works. No request was made for the (doubtless scarce even then) 1868 first edition, but a request was made for the subsequent 1880 edition which combined both volumes.

The copyright for Little Women expired in October of 1924. Louisa May Alcott had filed the copyright in the local federal court fifty-six years earlier, and just as the world had changed dramatically in those 56 years, the administration of copyright had changed dramatically as well, going from an obscure function of the federal district courts to a additional responsibility for the Librarian of Congress to the administration of a separate Office within the Library.

- Prior to this the registrant had to send deposits to DC themselves, leading to abysmally low rates of deposit even though the postage was free ↩

- The Copyright Act of 1870, § 88, states that the renewal term accrued to the “author, or his widow or children,” but provided no provisions for otherwise having the copyright renewed postmortem. Drone on Copyright, from 1879, suggests a strict reading of the statute is possible and that an assignee of the renewal right would not be able to exercise it. This was remedied by the 1909 Copyright Act, § 23, but that was far too late for Louisa May Alcott. Note that the gendered language of the 1870 Act would have been interpreted to apply to women as well, under the caselaw of the time including Silver v. Ladd, 74 U.S. 219 (1868). ↩

So WHO owns the copyright today? A new reader would like to know.

The books themselves have been public domain for almost a hundred years. Different publishers and editors may have a copyright in specific editions though.

I too was looking forward to the copyright scene (having heard about it from a student) and then when it came it made me so angry I couldn’t concentrate on the last, lovely, sequence of the film where the books get made. Honestly, if screenwriters don’t understand/can’t explain copyright law what hope is there for anyone else?

BTW I love this post.

So, I still haven’t actually seen it yet, but I understand it garbles the story a fair bit. With the home video release I’ll be able to comment with more authority 🙂

Glad you enjoyed!

Where is everyone angry about the copyright scene!?

The film was directed and adapted for the screen by a woman! Not only that but she wanted to pay tribute to such a strong woman as LMA, by showing that she didn’t ever actually marry, and that she owned the copyright to her own book, for the rest of her life! That is extraordinary for that time! The only different in the film vs real life is that in real life, supposedly the publisher suggested she keep the rights to her novel. However, that was very uncharacteristic of the time period. And I’m sure other publishers would have tried to “steal” the book from under her if they knew they could make a profit!

Men always change scripts and stories to suit male characters. I don’t see why women shouldn’t be allowed to do so as well.

I enjoyed the film, the direction and the story!

Fair point! I personally wasn’t so much angry as pedantic about the change, but I understand Prof. Alexander’s feelings, I think. It’s literary license but it obscures the reality of LMA’s existence in a literary circle in New England at the time.

My apologies for all of the grammatical errors. 😳 Maybe I need an editor?

Thank you for this post! I enjoy seeing old, original documents and thinking about the people involved as they went about their day so long ago. I loved learning about a new aspect of “Little Women” and Louisa May Alcott I didn’t know about before.

I came across your post when I was searching to make sure the characters of “Little Women” are in the public domain, as well as the book itself. I would assume so, but haven’t come across anything definite yet.

Thanks again for an interesting article.

So, the book and the characters as embodied in the book are in the public domain, but elements of subsequent adaptations which are not in the book may still be protected. If you have something specific in mind you should definitely get legal advice from your lawyer.

Thank you very much for your reply. Both your article and comment are very helpful. Fortunately, my focus is only on the book (with characters in my story portraying Jo March, etc in a play). I’ll look forward to reading future posts as I’m now subscribed to your blog. I enjoy this new aspect of learning about history. Thanks again!

Wonderful! I hope you enjoy – some of my posts are just aimed at lawyers, but others have a broader appeal.

This is a wonderful bit of information for Alcott fans and scholars! Thank you very much!